My favourite game of all time is Ultima Underworld, a first-person RPG set inside a massive underground prison known as The Stygian Abyss. It was released in 1992 for MS-DOS, and I remember being captivated watching my dad play it as I was growing up. The atmosphere is eerie and claustrophobic, the characters and lore are engaging, and there’s tons to explore. It was also a great feat of technology for the time, featuring the first texture-mapped 3D dungeon with incines, jumping, and the ability to look up and down.

If I could have the source code for any game, it would be this one. I’d love to port all the game systems to a modern engine, rework the clunky control scheme, and even rework it for VR. Alas, the game is locked away and doomed to only ever be played through DOSBox in its original presentation. There have been a handful of exciting fan-projects from people who have decoded the data file formats, created map editors, and even patched in mouse-look controls. There’s also a fantastic Unity port nearing feature-completeness, but it’s had to be engineered largely from best-guesses and observed gameplay.

The only way for us to know truly how the game works, then, is to examine its compiled code through disassembly and decompilation. As I’ve learnt over the past 10 hours or so, this is a very time consuming process that requires a lot of low-level technical knowledge. I don’t anticipate getting much further than I have, but it’s been an interesting exploration into what it takes to mod a game this way. So, here’s what my process has been, and what I’ve learned!

Disassembly

Ultima Underworld itself consists of a 16-bit MS-DOS executable (.exe) file, and a bunch of data files containing sprites, sounds, maps, and entities. From this we can already deduce that ‘UW.EXE’ is a game engine by itself, with the actual content of the game existing in these data files that get loaded at run-time. My interests lie in knowing how systems work, like character movement and script execution, so this is where I’ll be looking.

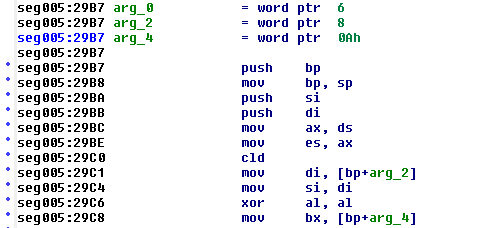

For the actual disassembly, I tried two programs: IDA (Interactive DisAssembler) and Ghidra. They both achieve similar things by analysing a binary executable and displaying it as a series of assembly instructions, with a bunch of other helpful analysis like decoding function headers, marking the beginnings and ends of subroutines, and presenting them as graphs. While this all certainly is incredibly useful, there’s a lot of hard work left to do.

What we’re left with is a LOT of 16-bit x86 assembly code. Each line is a single instruction that your CPU will execute that takes either one or two operands, which may be memory registers, memory addresses, or constant values depending on the instruction. For example, add sp, 4 will add 4 to the value stored in the ‘sp’ (stack pointer) register. IDA can decode this much as each instruction has a corresponding op code in the binary. The previous example, for instance, would look like 83 C4 04 in the binary, where ‘83’ is the op code for ‘add’, ‘C4’ is the identifier for the stack pointer, and ‘04’ is the constant value 4.

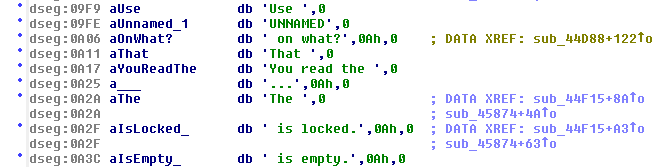

x86 Assembly is a massive topic that I could probably spend a long time learning about, so instead let’s move onto something a bit more understandable. IDA has also kindly found a list of raw strings present in UW.EXE. Scrolling through them, we can see some references to the data files mentioned earlier, as well as some in-game text indicating that many of the game’s behaviours are hard-coded in the engine. What’s more is that IDA has identified where some of these strings are being referenced!

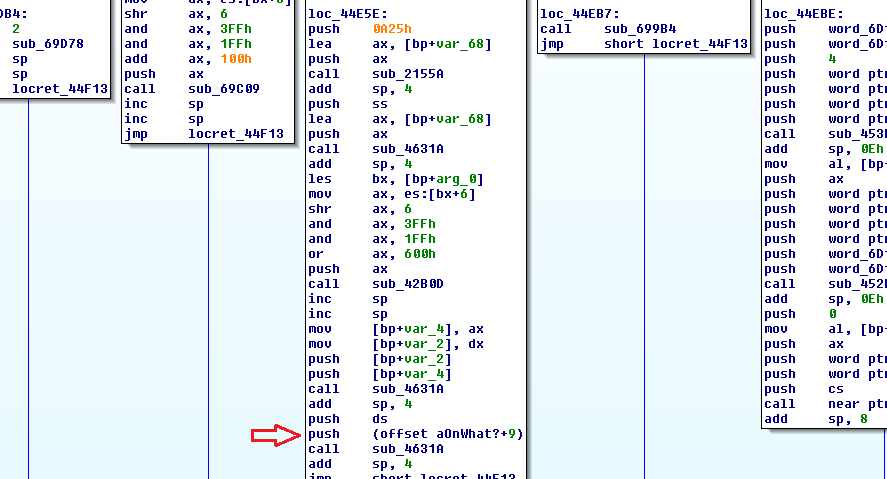

We can see that the string “ on what?” is being referenced by one place. From playing the game, I know that this string is shown when you select an item to use, such as a key, as the game asks you what you would like to use it on. Obviously this is only a fragment of a whole sentence, so we can assume that this will be combined with a couple other strings at some point. If we jump to this cross-reference, we can see where the string is being called in the assembly.

Here we can see that a bunch of stuff happens, then the memory address of the end of our string is being pushed to the stack, and then some more stuff happens. I can take a pretty rough guess that this string may be combined with another around here, or even just drawn directly to the dialogue scroll in game. This is cool, but it’s a bit overwhelming to look at as I’m not at all familiar with assembly. At this point, I decided to take a detour to try out something cool in DOSBox.

DOSBox Debugger

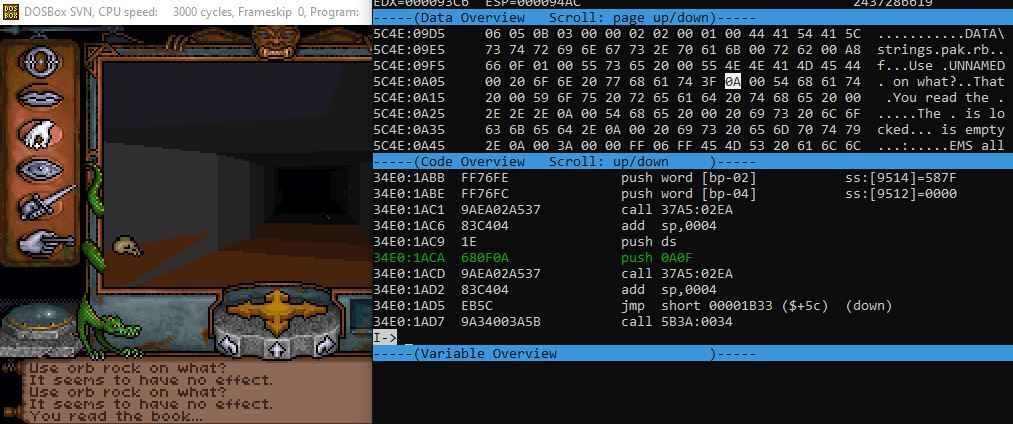

DOSBox is an emulator for MS-DOS applications, as modern operating systems aren’t able to run them. It also has a very handy debugger, which we’re going to use to breakpoint on the exact ‘push’ instruction that we found referencing the “ on what?” string. The debugger allows you to specify a segment and offset to breakpoint on, which will pause the application when it tries to execute the instruction at that location. IDA tells us that we’re looking for ‘seg040:1ACA’. From my limited experience, the use of segmented memory like this is only really found in old 16-bit applications, as one segment could only contain up to 65,535 instructions and operands.

Unfortunately, I don’t know where ‘seg040’ is. DOSBox expects a 16-bit number there, but IDA hasn’t given me one. This is because DOSBox will load the application segments with its own offset, so I need to find what this offset is and then add it to the file offset at the beginning of the segment that IDA shows. The process for this was a bit fiddly so I won’t go into detail here, but I eventually found it to be -017E. So, now I can find the file offset of seg040 (365E) and subtract 017E to get 34E0. So, I can now set a breakpoint in the DOSBox debugger by typing bp 34E0:1ACA. And then, when I try to use a key in-game…

There it is! There’s the push call to the memory address at the end of the “ on what?” string. By also finding the segment offset for the string, I was able to locate the data in memory that the instruction is pointing to. There wasn’t really much point in me doing this, but it was pretty satisfying to correlate the disassembly to runtime. If I wanted to, I could alter some code or memory whilst the program is paused to see how I could modify the game - this is exactly how you’d patch some bug or break some old copy protection. For now, though, I just wanted to play around a bit.

Ghidra Decompiler

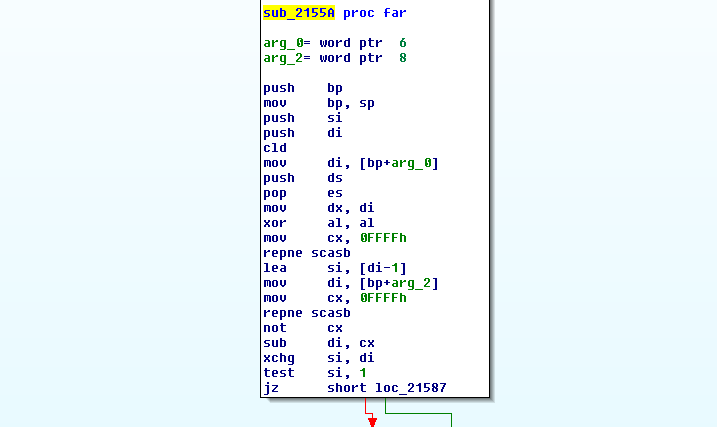

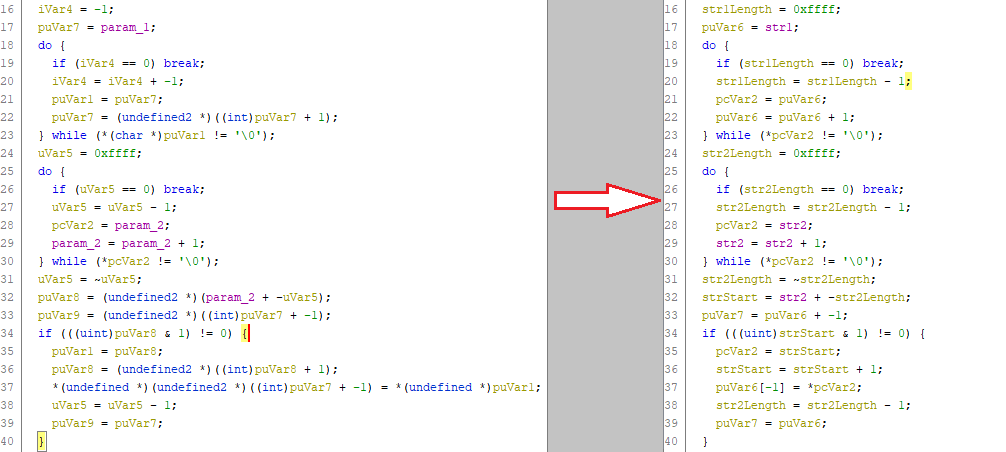

One last thing I looked at was the decompiler in Ghidra. Ghidra is a lot like IDA in what it can do, and each have their advantages. Ghidra can attempt to decompile the assembly code into more human-readable pseudo-C-code, which looks very powerful. I picked a small function that I saw in the surrounding code to see if I could work out what it does.

The first thing that stuck out to me here was the cryptic instruction “repne scasb”, which some googling told me stands for “REPeat while Not Equal - SCan A String (Byte)”, which will loop through the characters in a string until a given character is found - the string and character must be put in specific registers first. In Ghidra’s decompilation, these “repne scasb” instructions are expanded into do-while loops that continue until the string terminator character ‘\0’ is found. Like a master detective, I can now start filling in the names of the variables in the decompilation to uncover the true nature of this function.

It was around this point that I finally acknowledged that I’m not going to be able to achieve what I want without spending years combing through this code and mastering assembly. It’s been very interesting though, and I’ve learnt a few key points about hacking video games that I’m sure will come in useful in the future:

- Any raw strings and system calls in your code are breadcrumbs for hackers

- Assembly is a bit tricker than I thought

- Some people are really, really clever

For now, I’ll just keep my fingers crossed that the Ultima Underworld source code will magically appear one day.